|

| Steamy history streaming on Netflix Alfonso Herrera (L.) and Emiliano Zurita |

But to Mexican society back then, which was marked by a deep schism between the elite upper crust of the citizenry and the impoverished, the true scandal that is part of Mexico’s history emerged: a discreet gay ball where nearly half of the all-male participants wore women’s garb.

Directed by David Pablos, written by Monika Revilla and produced by Pablo Cruz and El Estudio, the 2020 film, dubbed in English, was based on a true story. Ignacio de la Torre y Mier, a politician (played commandingly by Alfonso Herrera), was appointed to Congress by Mexico’s president Porfirio Diaz (Fernando Becerril). The only condition of this appointment was that Ignacio make his daughter Amada Diaz (Mabel Cadena) happy.

It didn’t work.

Ignacio encountered Evaristo “Eva” Rivas (Emiliano Zurita) at the building where he works, and it was instant magnetism. Both sporting classic handlebar moustaches carry out their attraction secretly in steamy trysts. As this relationship tightens, the marriage between Ignacio and Amada unravels. Sex between the husband and wife was rare, strictly physical and devoid of any emotion or romance.

Amada becomes increasingly suspicious of Ignacio’s “late dinners” with friends as he typically doesn’t return to their palatial estate until early the next morning. Later she discovered love letters to Ignacio from Eva and demanded he provide her with a child or she will reveal everything.

But it’s not just the dalliances with Evaristo that occupies Ignacio’s time. Apparently known to the underground gay community of Mexico City prior to his marrying the president’s daughter, Ignacio was invited to become a member of a secret gay private club complete with a brief initiation ritual in the spacious house of one its members. Ignacio soon brought Evaristo to the festivities thereby becoming its 42nd member.

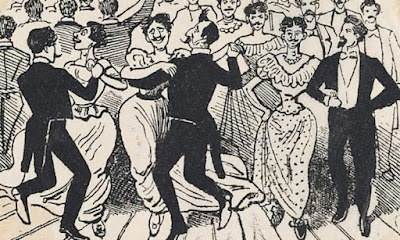

The members, displaying various levels of flamboyance and camp, engaged in orgies that took place in and around half dozen bathtubs, sing-alongs, drag cabaret performances and the like while booze flowed freely. On November 17, 1901, the annual ball took place from which the title of this film was derived.

SPOILER

Rumors swirled around society concerning Ignacio’s behavior. Bodyguards were assigned to him, and he was being followed. During this ball, armed police raided the party. According to a contemporary press report:

On Sunday night, at a

house on the fourth block of Calle la Paz, the police burst into a dance attended

by 41 unaccompanied men wearing women’s clothes. Among those individuals were

some of the dandies seen every day on Calle Plateros. They were wearing elegant

ladies’ dresses, wigs, false breasts, earrings, embroidered slippers, and their

faces were painted with highlighted eyes and rosy cheeks.

The film accurately portrayed the incident.

Though there was nothing illegal about men dressing up as women, the 42 men were arrested for violating the principles of morality and to appease an already distressed society. There were no trials; the punishment was meted out by Governor Ramon Corral—a fact that was not included in the film.

Only 41 were officially counted. As the security chief recognized Ignacio, he was allowed to escape to

spare embarrassment to the government. Others, including Evaristo, were beaten and forced to sweep the streets in their women’s attire. They were eventually sent to work for the military doing menial tasks.Throughout the decades, the number 41 was considered taboo.

“At one point the Army left the number out of battalions, hotel and hospital rooms didn’t use it and some even skipped their 41st birthday altogether," reports history. com. "While the number was etched into society as derogatory, 41 is now considered a badge of courage and a symbol of strength for queer Mexicans.”

One might consider the "Dance of the 41" Mexico’s Stonewall, although any liberation for LGBTQ+ Mexicans did not occur until over a century later.

Dance of the 41 is highly recommended. The accurate depiction of historical events makes it worthwhile, and the cinematography, direction and acting talents displayed enhance its excellence.

No comments:

Post a Comment